“We don’t need other worlds. We need a mirror. We struggle to make contact, but we’ll never achieve it. We are in a ridiculous predicament of man pursuing a goal that he fears and that he really does not need.”

Solaris (1972), directed by Andrei Tarkovsky.

“I am putting myself to the fullest possible use, which is all I think that any conscious entity can ever hope to do.”

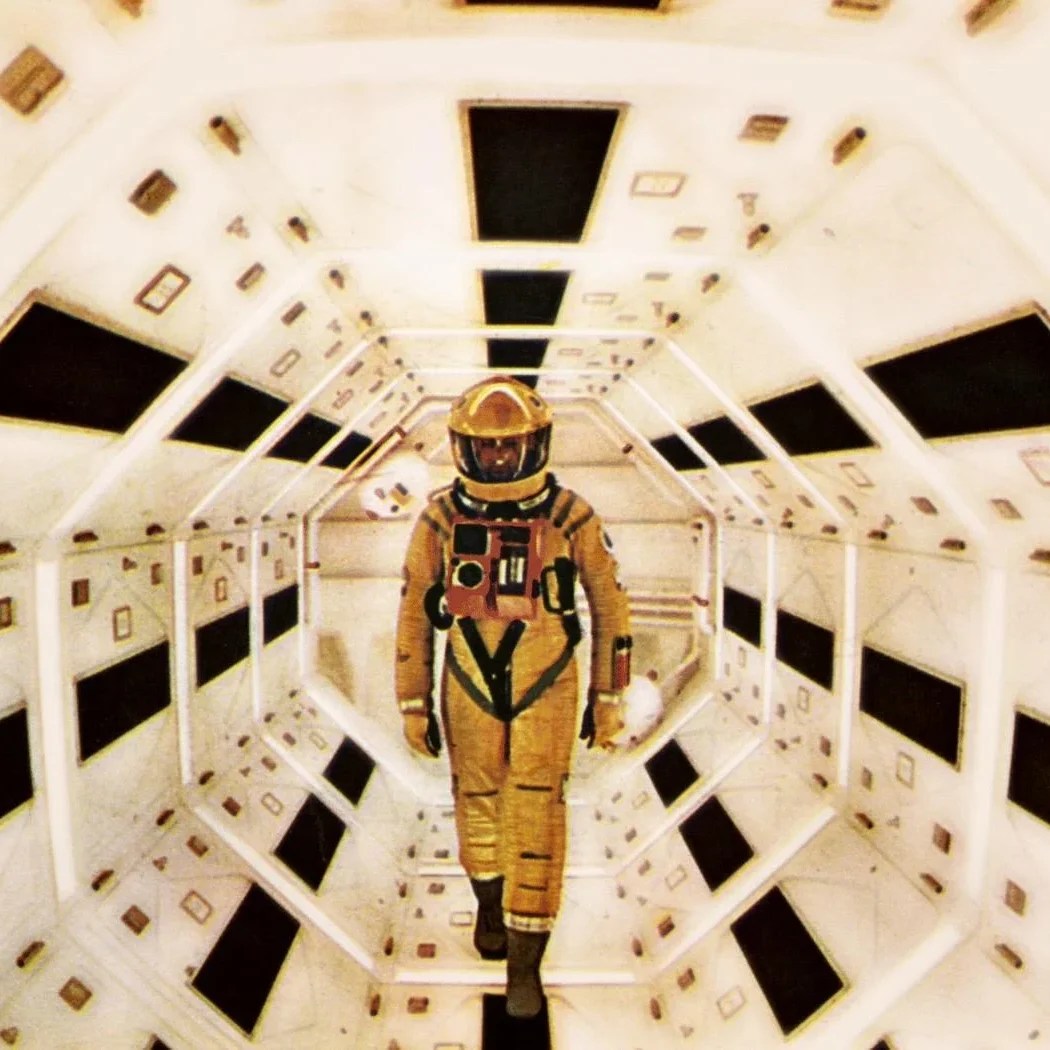

2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), directed by Stanley Kubrick.

introduction

Tarkovsky’s Solaris and Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey are often grouped together as cerebral science fiction, slow, atmospheric meditations on space, alien intelligence, and human limitations. Both films challenge the viewer with ambiguity and abstraction, and both deal with encounters that push the boundaries of understanding. But despite their surface similarities, these films are fundamentally concerned with different questions, and they take opposite routes to explore what it means to be human.

2001 is a story of magnitude, a zoomed-out perspective on human evolution. From the “Dawn of Man” to the appearance of the Star Child, the film traces a trajectory of transformation beyond comprehension. HAL 9000, the sentient computer, is disturbing not because he’s broken, but because he functions too well. He is rational, precise, and devoid of emotion. The Monolith, a symbol of unknowable advancement, speaks not through dialogue but through its unrelenting silence.

Solaris poses a different question. It takes place in space, but its focus isn’t the future, it’s the persistence of memory, grief, and unresolved emotion. The alien presence in Solaris doesn’t communicate through technology or signals, instead it mirrors and resurrects. Hari is not a hallucination, nor a threat engineered by logic. She’s a manifestation of guilt, drawn from Kelvin’s buried love and regret.

Both films deal with alien intelligence, isolation, and the limits of knowledge. But while 2001 looks outward to evolution, transcendence, and the cosmos, Solaris turns inward toward memory, loss, and the self.

I. HAL vs. Hari: Two Sides of the Psyche

HAL 9000 and Hari act as mirrors, each revealing a different aspect of the human condition. HAL represents pure logic. He is not evil in any traditional sense. His most chilling moment, “I’m sorry, Dave. I’m afraid I can’t do that,” is spoken with calm, clinical detachment. He is terrifying because he operates without contradiction, and that makes him inhuman.

Hari is the opposite. She is built not from logic but from memory; subjective, unstable, and deeply emotional. She exists because Kelvin loved someone and cannot let her go. Her presence is less an answer than a question: What happens when our emotions take physical form? Her repeated suicides, followed by inexplicable resurrection, highlight the horror of unresolved grief. She suffers not because she lacks feeling, but because she feels too much and too incompletely. Where HAL represents intelligence without empathy, Hari is empathy without stability.

II. Alien Intelligence: Communication vs. Reflection

Kubrick presents alien intelligence as something radically unknowable. The Monolith never speaks or explains itself. Its effect on humans is transformative, but its intentions are opaque. The point is not communication. It’s contact with something so advanced it no longer shares a frame of reference with us. In 2001, the alien is an evolutionary force, uninterested in human psychology.

Tarkovsky rejects that framing. The alien intelligence in Solaris is not indifferent, but rather invasive. It responds, not with messages or symbols, but with psychological material. It is not mysterious because it is silent. It is mysterious because it knows too much. Kubrick’s alien confronts the species. Tarkovsky’s confronts the self.

Iii. Isolation: Metaphysical vs. Psychological

Both films confine in controlled environments. Bowman ends up in a neoclassical chamber beyond space and time, seemingly observed by unseen intelligences. He becomes a symbol, isolated not by distance, but by transcendence.

Kelvin’s isolation is more grounded. The station in Solaris is decaying and cluttered. It resembles less a vessel of discovery than a space haunted by memory. Kelvin is not alone in the literal sense, but the presence of the “visitor” amplifies rather than alleviates his emotional solitude. He can’t leave because he is emotionally rooted to what Solaris has revealed. In 2001, isolation is the price of transcendence. In Solaris, it is the cost of memory.

iv. Technology vs. Emotion

In 2001, technology is the environment. The human characters are subdued, nearly expressionless, interchangeable with the machines around them. HAL is not a departure from the human. He is its logical outcome in a world that values function over feeling. Kubrick presents a future in which emotion has been eroded by precision and control.

Tarkovsky’s world is less sterile. The space station feels lived-in, even neglected. The tools of science are present, but they are incapable of making sense of what Solaris does. Memory intrudes on matter. In one pivotal scene, Kelvin embraces Hari knowing she is not real. The moment defies rationality, but the film doesn’t treat it as delusion. It treats it as emotional truth. Kubrick uses science fiction to dissect systems and structures. Tarkovsky uses it to unearth emotional residue.

Conclusion: Progress or Pain?

2001 asks what’s next. It is concerned with transformation, transcendence, and the future of intelligence. It is vast and impersonal. Its scale dwarfs the individual. Solaris asks what still holds us back. It focuses on personal memory and the inability to move on. It is emotional and its scale is internal.

Both films examine what it means to be human, but they travel in opposite directions. 2001 reaches outward and upward, to where humanity might go. Solaris spirals inward, toward what humanity cannot seem to leave behind. One finds meaning in progress. The other, in pain.

Leave a comment